Project Humanities tackles how to make food more accessible, equitable to everyone

While there’s a long history of communities growing their own food, there’s been a recent uptick in people finding alternatives to the grocery store.

In fact, there’s a whole generation of influencers using social media to teach people how to grow and find food in their homes, backyards, greenhouses and community gardens.

This is what scholars and community members refer to as food sovereigntyFood sovereignty is a food system in which the people who produce, distribute and consume food also control the mechanisms and policies of food production and distribution. Source: Wikipedia.. It was the subject of a March 1 Project Humanities livestream event called "Food Sovereignty and Farming as Resistance."

“A lot of people think about gardening as a hobby or a way to spend less at the grocery store. But for Indigenous, Black and other people of color, food sovereignty is about decolonial practices and approaches to restoring traditional cultural knowledge, protecting the environment, restoring health and economic independence,” said Alycia de Mesa, associate director of Project Humanities and event facilitator. “Choosing what you eat, where it comes from and how food is grown, preserved and prepared allows individuals, tribal and urban communities to promote and benefit from cultural, health, economic, environmental and social well-being.”

De Mesa facilitated a panel that included Jameela Pugh, a Black Arizona farmer and the owner of EnviroFarm Ranch Market; Jacob Butler, a member of the Salt River Pima Maricopa Indian Community and chair of Native Seed search, a Tucson-based seed conservation organization; Twila Cassadore, a member of the San Carlos Apache Tribe and professional caterer and food vendor; George Brooks, founder, president and CEO of NxT Horizon, an ag-tech consulting firm that grows healthy food; and Angela Brooks, a master gardener who is widely known as the “Green Garden Chick” on social media and uses her platform to offer farming/gardening/eco-friendly tips to followers.

The panel discussed a wide variety of topics, such as food justice, health, culture, colonialism, slavery, sustainability and the pandemic.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, food sovereignty has been making a big comeback. Some of the appeals include reduced carbon footprint, self-sufficiency, better health and the opportunity to serve others in the community.

Project Humanities Associate Director Alycia de Mesa (top center) moderates an online panel on food sovereignty and farming as resistance on March 1. Panelists include George Brooks (top left), Jacob Butler (top right), Angela Brooks (lower left), Twila Cassadore (lower right) and Jameela Pugh, who joined later in the event.

“The pandemic was an awful circumstance, but it made people reprogram how to live, how to survive,” said Angela Brooks, who owns Millbrook Urban Farms in South Mountain and grows a variety of herbs, fruits, flowers and vegetables. “I saw a great surge in self-sufficiency gardening, and it was wonderful.”

Twila Cassadore said Indigenous peoples have a rich history of farming, and the land informs them of what they should eat and what to grow.

“Beautiful greens are growing out there in the mountains right now, including three species of lettuce,” said Cassadore, a traditional forager who works on a number of community health issues and cultural preservation projects. “For every season there (is) a different variety of foods. … I let Mother Nature take care of the food she wants to give me.”

Cassadore said Mother Nature got interrupted in the mid-1900s with the mass production of farming, and suddenly growing your own food was frowned upon.

“This economic industry came in and shunned people away from that because they didn’t want to be stereotyped as poor,” Cassadore said. “It changed the mindset of people where if you could not buy from the grocery store, ‘You must be poor.’”

Shoppers have also complained about the high price of organic food and meat, but they don’t know about love and sweat that goes into harvesting the crops or keeping the animals, Pugh said.

“Someone will come into my store and order five chickens and I tell them the price. I tell them and they say, ‘Wow, that’s expensive!’” Pugh said. “But if you go into a big agricultural store where you don’t know where it came from, what it was eating or how it was treated, and you’re just looking at the $2.99 per pound price rather than the quality, it is a big difference. But if they try it and see a huge difference in their health, it’s worth it.”

Right up to the pandemic, people have lost their connection to where their food comes from and how it’s grown, said Jacob Butler. But, he added, they’re starting to get it back.

“We need to develop a better relationship with the environment and the things that grow within it,” said Butler, whose organization frequently visits homeowners and teaches them how to grow a personal or community garden and gives them the seeds to start. “Within two months, you can be eating from your own crops, and that’s an awesome thing.”

George Brooks said now that attitudes toward food sovereignty are starting to turn the corner, many people want to get into farming but can’t because of a variety of roadblocks.

“I have sat in rooms full of people in urban areas who want to get into the business of agriculture,” Brooks said. “Yet they can’t because they don’t have the land or don’t have the money in order to make a profit. This is what they’re told, so they give up at this point.”

Angela Brooks said that people can come by and take a taste of her food, but at some point they’ll have to pick up a hoe or gardening tool and get their hands dirty.

“Yeah, you’re going to work for your food, because I want people to feel it, eat it, taste it, digest it,” said Brooks, who runs a community garden at her home and grows watermelons, onions, bell peppers, tomatoes and edible flowers. “Touching, feeling, smelling and eating what real food tastes like is a game-changer for people.”

Top image courtesy iStock/Getty Images

Much of 2013–14 Euromaidan protests — Putin, democracy, the will of the people — is echoed in current war

Sometimes fiction can illuminate a real-life topic better than nonfiction.

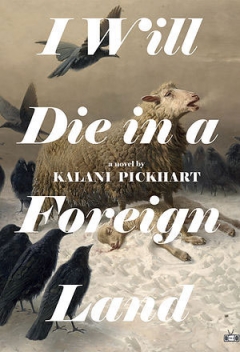

That's the reason Book Riot gave for including an Arizona State University alumna's novel about Ukraine as part of its list posted earlier this week of "Books for understanding Russia's invasion of Ukraine." Kalani Pickhart's lyrical "I Will Die in a Foreign Land," published this past October, was the only fiction entry on the list.

The novel takes place during the Euromaidan protests in Kyiv, which began in late 2013 and stretched into 2014, when hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians protested against then-President Viktor Yanukovych's decision not to sign a referendum with the European Union, choosing instead to build closer ties with Russia. The demonstrations and civil unrest would widen to encompass more rights and corruption issues. By the end of summer 2014, hundreds of civilians and dozens of police officers had been killed, Yanukovych fled the country, a new president was elected, Russia seized the parliament of Crimea, and Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 was shot downIn September 2016, an international team of criminal investigators said evidence showed the Buk missile had been brought in from Russian territory and was fired from a field controlled by Russian-backed separatists. Russia has denied any role. while flying over eastern Ukraine, killing all 298 aboard.

All of that is covered in a three-page timeline at the start of the book.

The rest of the novel follows more slowly and more personally the lives of four people whose paths intersect over the course of those protests and the months that followed — a Ukrainian-born doctor adopted by U.S. parents who returns to help at a makeshift medical clinic; a former KGB agent; a mining engineer whose life was forever altered by the Chernobyl meltdown; and a young activist who finds both love and grief.

The story dips in and out of their individual stories, interspering those chapters with lists of the dead, folk-song lamentations — based on the traditional kobzari, wandering Ukrainian bards — news reports and transcripts of cassette recordings. All the pieces add up to a novel that has garnered praise from a range of sources, from a starred review in Kirkus to a recommendation by a Washingon Post critic.

Pickhart has a number of ties to ASU: She finished her Master of Fine Arts with the Department of English in 2019. A first-generation college student, she also earned a bachelor's degree in English literature from ASU in 2009 and was a Barrett, The Honors College student. Now she works as a coordinator at the Design School, part of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts.

She spoke with ASU News about the inspiration behind her novel and how it came about.

Question: What first drew you to this nation and its history? What was your “aha” moment when you knew this was the story you wanted to tell?

Answer: As many people around the world are now witnessing, Ukrainians are tough people. They aren’t mincing words or actions with the Russian president and invaders. I watched a documentary about the 2014 protests in Kyiv called "Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Democracy," and I was simultaneously in my first semester in grad school, in a novel-writing course taught by Matt Bell. I was really moved by the story, and the sheer grit and fighting spirit Ukrainians have as a nation.

The moment I knew I wanted to write the book was the ringing of the bells at St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery in Kyiv: The last time all the bells had been rung, it was during the invasion of Kyiv from the Mongols in AD 1240 in order to warn the people of the attack. I found it especially heavy that they were being rung in 2013 against their own police force. There was something there I couldn’t shake.

Q: What kind of research and travel went into writing this book?

A: A lot! Because I’m not Ukrainian, I felt an immense responsibility to tell the story compassionately and accurately — it also became clear very quickly that even though I was writing a story that took place in 2013–2014, there was a ton of history that led to that particular protest, so I was doing a lot of reading to try to understand the context of the moment. Meanwhile, we were reading about two novels a week at the time, so a lot of ideas on how to write the book came from a few choice authors, with the most obvious being Milan Kundera’s "Unbearable Lightness of Being." I was fortunate to have this confluence of both logistical research and artistic influence — it helped me get a quick, bare-bones draft at the end of my first semester of graduate school.

I went to Kyiv and Prague on research and language fellowships the summer of 2018: one from the Melikian Center’s Critical Languages Institute through the U.S. Department of State, and the other from the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing. I took eight intense weeks of Ukrainian — easily the most difficult courses I’ve ever taken — and immediately left for Europe afterward. At one time, my Ukrainian wasn’t too bad! But I have certainly, regrettably, lost a lot of it now.

Q: Your book begins with a timeline of the events that were part of the Euromaidan demonstrations and unrest in late 2013 and into 2014. Why did you decide to start a historical fiction book this way?

A: This was a conversation I had with my publisher, Two Dollar Radio. I had originally made a timeline when drafting the book but removed it when I was sending it out to publishers and agents. I owe a lot of credit to Eric and Eliza (Obenauf, the husband-and-wife team that runs Two Dollar Radio) for thinking critically about this book — we decided a general timeline and a map would be helpful for American readers, especially since there’s a lot of movement. The timeline helps provide some more straightforward context that the kobzari and journalists touch on here and there.

The map was something my dad wanted, actually. He told me after reading it that it could use one because he wanted to be able to have a simple frame of reference since he didn’t know anything about it. I’m glad we included it — he was right. It’s strange right now seeing maps of Ukraine every day, everywhere. I check one every day on the movement of Russian troops. It’s surreal and incredibly sad.

Q: The structure of the book — not strictly chronological, with chapters of the four main characters’ action interspersed with news reports, lists of the dead and the lamentations of the kobzari — is unusual, and quite lyrical. It forms a tapestry of the story, rather than a strict timeline such as you put at the start of the book. What were your goals/thoughts in structuring it this way?

A: So, I mentioned that as I was doing research on this particular protest, I quickly realized that I was uncovering a long, intense historical context. I felt that in order for a reader to understand why these protests were so important, it was critical to provide that context so they realized what was at stake. Practically speaking, I didn’t want to have the people in the book — Katya, Misha and Slava — bogged down with that responsibility. There was no way to do it without it feeling heavy-handed or awkward. The kobzari sections and articles help fill in that context in a way that felt more natural — this omniscient and third-person perspective that knows more than the perspective characters do.

Q: You weave the history and effects of Chernobyl into some of the characters’ stories. How important is it to include Chernobyl in any story of Ukraine?

A: Chernobyl is a word that I think most people recognize, so I wanted to be careful with it. I didn’t initially seek to include Chernobyl in the book because I was afraid it would be too much of a “kitchen sink” book with everything significant in Ukrainian history. Everything needed to be intentional.

When I was learned about the old generation of survivors who did not leave their homes despite the radiation, the samoselyResidents of the roughly 20-mile Chernobyl Exclusion Zone surrounding the most heavily contaminated areas near the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant., things changed. The research for this book was really geared toward understanding the Ukrainian psyche as much as I could, and the particular fact about Pripyat’s samosley population organically reflected this protectiveness over home and the land of Ukraine that I was seeing pop up again and again through my studies. Ukrainians had been murdered by the millions because Stalin wanted their land, for example. There are a number of Ukrainian poems and laments from soldiers missing their villages while fighting for the Russian Empire — the significance of home and identifying as Ukrainian is profound.

The other reason I included Chernobyl was the fact of the negative influence of the USSR and the lasting effects of one of the largest environmental disasters in human history under ineffective and corrupt leadership. In 2013–14, Ukrainians were still trying to shake that Soviet influence and had been both literally and figuratively cleaning up for decades. You feel that significance in the novel even though it’s not blatantly stated.

How to help

There are many ways people can donate to help Ukrainians displaced and in need during the current conflict. Pickhart highlighted these groups:

Top photo: Protests in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Feb. 18, 2014, when Ukrainian police used tear gas, grenades and live and rubber ammunition on Euromaidan protesters in Independence Square, or Maidan Nezalezhnosti. More than 100 civilians and a dozen police officers were killed over the course of several days. Photo by Vadven/iStock

https://ift.tt/h5f1LKu

food

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar